The current state of America’s sharing economy is marked by increased tensions between new sharing companies and well-established business models. How local governments approach these economic disruptions will help shape the future of economic growth and how future business does business.

Local Governments and Positive Disruption: Leveraging the Sharing Economy for Sustainable Communities

“It’s going to take companies and governments that can sit down and work together to find the best way to maximize the economies and the platforms that will still allow the government to be able to deal with safety issues. We haven’t figured out that place right now.”– Mayor Steve Adler, City of Austin, TX

The current state of America’s sharing economy is marked by increased tensions between new sharing companies and well-established business models. How local governments approach these economic disruptions will help shape the future of economic growth and how future business does business.

Sharing operations have often run into conflicts with existing regulations and with other local businesses in the same sectors. For their part, local governments have struggled to find a balance between addressing safety, equity and liability issues and encouraging economic innovation and the growth of its revenue base.

With sharing firms becoming increasingly prevalent in communities across the nation, local governments should consider what policies for this new economic phenomenon are most valuable and effective for their communities. Consumer protection is important, and governments must also carefully assess other broader economic and equity goals. At the same time, the interests of sharing-economy firms and local governments can often align.

More than three-quarters of Americans (76%) who are familiar with the sharing economy believe it’s better for the economy, according to a 2015 PricewaterhouseCoopers study, where everything from underused cars and bikes to vacant rooms and abandoned toys that are being shared would otherwise sitting idle and are seldom used. Research is starting to show that the peer-to-peer economy may also have environmental benefits.

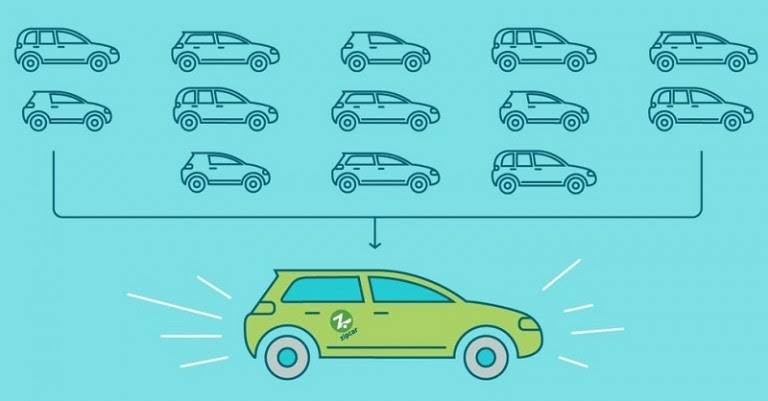

Carsharing has been correlated with reduced car ownership. A Transportation Research Board study found that “at least five private vehicles are replaced by each shared car.” The University of California Transportation Center puts the number higher, with 9 to 13 cars taken off the road. Even at its lowest estimate, removing cars from the road alleviates congestion. And because carsharing programs typically use newer models, they can also reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

The Transportation Sustainability Research Center report notes that among Zipcar carshare members who eliminated car ownership entirely, 41% use public transit more often, 41% walk more, and 22% use their bikes more often.

Airbnb says their rental guests are 10% to 15% more likely to use public transit, walk or bike as their primary mode of transportation than if they had stayed at a hotel instead.

City officials should carefully consider whether existing regulations can still provide the greatest community benefits in the era of the sharing economy, and how those rules might be adjusted accordingly. Likewise, sharing companies should work proactively with local governments to help develop standards, guidelines and programs that can provide mutual benefits.

Regulating Sharing Services in Good Times and Bad

Established business owners are most concerned about the unfair competition they claim sharing companies bring. To address this issue, some cities strike deals with sharing firms, such as requiring tax payment in return for allowing operations. Others try to level the regulatory playing field: Colorado and Washington, DC, required Uber to conduct more in-depth driver background checks and buy more comprehensive insurance. New Orleans now levies a standardized limousine tax on both Uber and non-Uber cars.

As a response to Hurricane Sandy and other natural disasters, Uber was pressured in 2014 to agree to stop raising prices substantially (they can still use “surge prices” but at a much lower and controlled rate) during natural disasters and states of emergency. Uber has subsequently implemented this solution on a national scale, and will donate the surge commission it earns on fares during natural disasters and emergencies to the American Red Cross.

Airbnb uses its Open Homes program to connect hosts with evacuees during natural disasters like the recent Northern California firestorm (while waiving all booking fees). Its hosts within a given distance from the disaster were encouraged to make their unused homes and rooms available for free or at a discount to displaced neighbors and emergency responders.

Another major cause for concern within communities is regulating areas of growing traffic congestion. Delivery trucks, bike lanes, parking spaces and ride-share services all play a part in the curbside ecosystem. Washington, DC’s Department of Transportation partnered with the Golden Triangle Business Improvement District to test a few solutions. During the pilot, daytime curbside parking spaces are converted to ride-share pick-up/drop-off zones on weekend nights.

Fort Lauderdale implemented designated ride-share zones as part of its six-month plan to boost safety and mobility along the popular Las Olas Blvd. corridor. The plan includes new daytime-delivery loading zones to discourage double parking and unloading in travel lanes. Some of the zones transition to parking spaces in the evenings.

Sharing Local-Government Strategies

How do we leverage a complex web of subsidies, taxes, regulatory redistribution and reliance aimed at using sharing firms to achieve key community goals? A study by Daniel E. Rauch and David Schleicher, professors at the Marron Institute of Urban Management, outlined a few mutually beneficial scenarios for how municipalities and sharing firms could grow businesses and help the community.

- Subsidize sharing firms to get them to enter or expand certain service.

Through the Oregon-based Getaround app, the first car-sharing program to receive a federal grant, owners can rent out their cars to others. In the past seven years, the program has spread to other cities like San Francisco, Berkeley, Oakland, Chicago and Washington, DC.Parking is also a factor to consider. Current regulations often require stores to provide enough parking spaces to accommodate “peak hour” traffic. This results in vastly excessive parking spaces much of the time, increasing the costs of construction, housing, office space and retail goods. If sharing firms like ParkingPanda or Uber and Lyft reduce the number of shoppers who need to park, inefficient parking spaces can be repurposed into better community uses. - Harness sharing firms to distribute services and benefits more equitably.

In theory, sharing firms can offer important benefits to lower-income residents, including access to otherwise unaffordable goods or new work opportunities.However, this potential is largely unrealized so far: sharing firms have concentrated their marketing and operations on upscale consumers even though, in cases like car-sharing, underserved communities accounted for 35-40% of Uber trips nationwide the past year. In New York City, 40% of Uber rides serviced individuals in the outer boroughs. In Chicago, 50% of UberX rides begin or end in underserved neighborhoods.Cities should take steps to increase benefits to low income residents by influencing sharing firms to bring their redistributive potential to the forefront. Requirements have long been implemented as a condition for approval for zoning changes that provide redistributive services like affordable housing. For example, cities could link permit approvals to some form of in-kind redistribution, such as requiring discounted taxi service in lower-income areas or requiring short-term hiring services to give unskilled workers a form of job training.First mile/last mile

For local governments that want to help bridge the first mile/last mile transportation divide, ride-hailing services are also emerging as crucial last-mile connectors to areas beyond the public transportation hubs and are providing a necessary link for communities that don’t have transit options. One-half of Uber’s car-sharing trips are one way, which indicates that riders rely on ride-sharing services like Uber to fill the gap.In Solano, California, Lyft launched a jobs-access program that allows transit riders to connect from the local Amtrak station to job parks up to five miles away. Clients use the service along with other taxis and public transits to get to work, school or childcare.

To alleviate congestion around the new Golden 1 Center in Sacramento, Sacramento’s Regional Transit District an Lyft teamed up to provide discounted rates to arena-goers.

Paratransit services

Governor Baker and MBTA launch innovative program to enlist Uber and Lyft to better serve paratransit customers.

In Massachusetts, Lyft and Uber partnered with the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority to offer paratransit customers on-demand service. The agency maintains a $100 million annual budget for Boston’s door-to-door service, known as The Ride. Partnering with Uber and Lyft reduces the per-person cost to the state from $31 to $13 a ride, indirectly allowing the state to invest the difference in other public-works infrastructure. - Hire sharing firms as contractors to provide local services.

Government contracts could provide local governments further leverage with sharing firms. Many of them use car-sharing companies to cut the cost of providing city vehicles. Boston, Houston and Washington, DC, and even federal agencies, have contracted with ZipCar to run their car fleets as car-sharing opportunities among public servants.Chicago pays for ZipCar or other car-share membership on behalf of its City employees. San Francisco is considering abandoning its non-emergency fleet entirely in favor of car-sharing vehicles. Some agencies have even begun to form their own sharing operations. Munirent, a service that emerged in Michigan and Oregon, allows governments to share all sort of government-owned heavy-duty equipment.Many federal and state workers who must abide by certain rates when traveling are turning to Airbnb to stay within per-diem rates.

Engaging the Future of Disruption

The future of the sharing economy – and local attempts to regulate and benefit from it – will be very different from today’s sharing landscape. The changes will pose profound legal, political and ethical questions for local communities.

When it comes to industries at the core of connectivity – transit, housing, energy, consumer retail and others – if there’s anything we can learn from past industry disruptions, it’s that local leaders have the political power and the economic incentives to be thoroughly involved in its future.

Resources

- Chris Lehane, Head of Global Policy and Public Affairs, Airbnb Presentation at NPSG 2/1/18

- Joseph Okpaku, Vice President of Public Policy, Lyft Presentation at NPSG 2/1/18

- APA Shared Mobility Report

- The Future of Local Regulation of the Shared Economy

- Los Angeles Mobility Plan 2035

Local Government Commission Newsletters

Livable Places Update

CURRENTS Newsletter

CivicSpark™ Newsletter

LGC Newsletters

Keep up to date with LGC’s newsletters!

Livable Places Update – April

April’s article: Microtransit: Right-Sizing Transportation to Improve Community Mobility

Currents: Spring 2019

Currents provides readers with current information on energy issues affecting local governments in California.

CivicSpark Newsletter – March

This monthly CivicSpark newsletter features updates on CivicSpark projects and highlights.